Tom Sparks

Director, Just Access

Sometimes, even as events unfold, you can sense history weighting the present, writing events into our collective memory as deeply as chiselled stone.

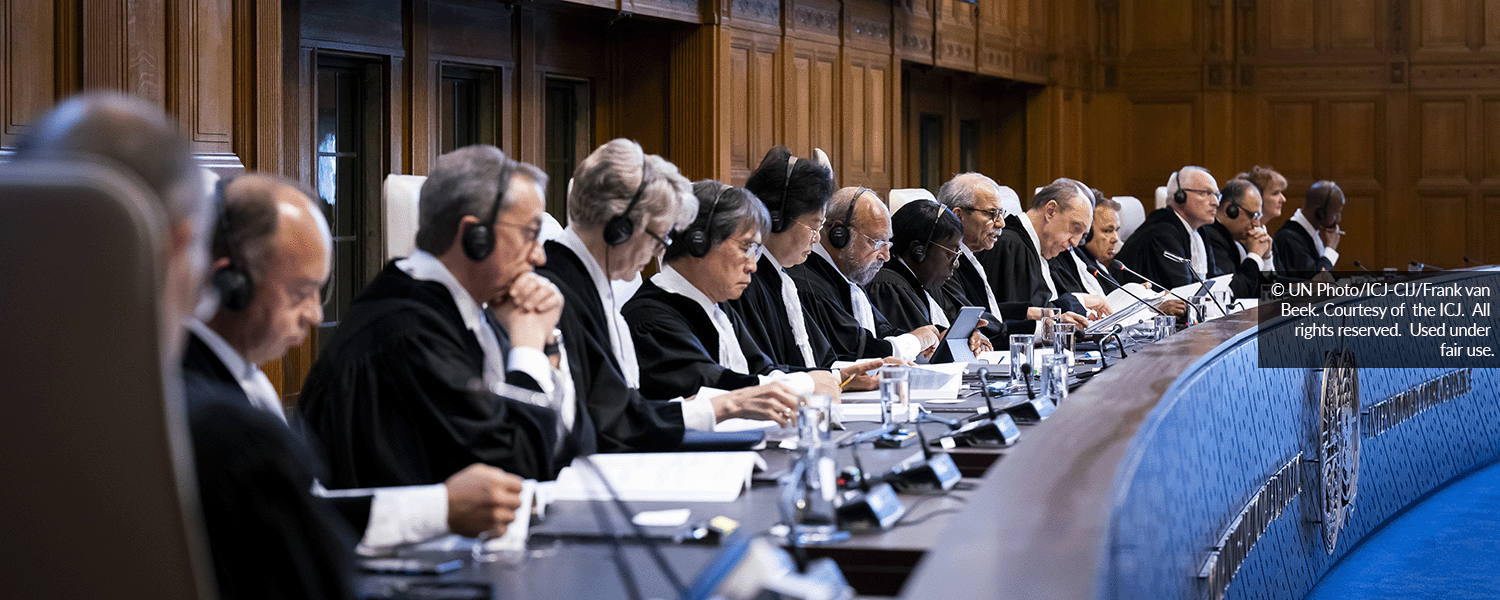

That was the momentous, breathless atmosphere that held sway as Judge Nawaf Salam, President of the International Court of Justice delivered the CourtŌĆÖs advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences Arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem.

Advisory opinions from the Court are always significant moments.┬Ā The ICJ is the highest court dealing with questions of international law, and its pronouncements carry enormous weight.┬Ā Unlike the other side of the CourtŌĆÖs workŌĆöso-called ŌĆścontentiousŌĆÖ casesŌĆöwhere two or more States might bring a dispute to the Court and ask it to resolve the key legal and factual questions at issue, advisory opinions are the CourtŌĆÖs response to requests for advice from the UN General Assembly, the UN Security Council, and a strictly limited number of other organisations.

Rather than resolving a dispute, when it is issuing an advisory opinion, the Court is asked to give an authoritative interpretation of what international law says on a topic ŌĆō almost inevitably, a highly controversial topic.┬Ā From decolonisation to the powers of the UN, self-determination to the situation in Kosovo, many of international lawŌĆÖs most difficult questions come before the Court, sooner or later.┬Ā A case in point, the ICJ is currently faced with another advisory request, on States’ obligations in respect of climate change, which has the potential to be quite simply world-changing.

The Palestine advisory opinion could hardly be more significant.┬Ā The Court declared that IsraelŌĆÖs presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) is unlawful, that Israel must dismantle its settlements in the OPT, and that Israel owes reparation to the people of Palestine for the harm it has done to them.┬Ā Moreover, the Court found that all States are under an obligation to refrain from aiding or assisting Israel to maintain its illegal presence in the OPT.

Notably, the judges on the bench were remarkably unified in making these findings, notwithstanding their significance:┬Ā of the fifteen judges on the Court, only one JudgeŌĆöJulia Sebutinde of UgandaŌĆövoted against all the substantive findings, and the narrowest majority was the finding, by eleven votes to four, that IsraelŌĆÖs continued presence in Palestine is unlawful.

Today, the ICJ made history once again. The decisions of the 2023-2024 bench will be studied by students for years to come. Most importantly, this legacy should not merely endure as history but demonstrate the power of law to deliver justice and create a better world

— Julia Emtseva (@j_emtseva) July 19, 2024

This was a wide-ranging opinion, every paragraph of which was significant.┬Ā For years to come, legal scholars will pour over the document, but for the purposes of this post, IŌĆÖll focus in on just two aspects.

Racial Segregation and Apartheid:

the Court declared that IsraelŌĆÖs conduct in the OPT breaches Article 3 of the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, which requires States to ŌĆśprevent, prohibit, and eradicateŌĆÖ ŌĆśracial segregation and apartheidŌĆÖ.┬Ā Although the Court stopped short of using the term ŌĆśapartheidŌĆÖ, it declared that IsraelŌĆÖs use of legislative and practical measures which ŌĆśimpose and serve to maintain a near-complete separation in the West Bank and East Jerusalem between the settler and Palestinian communitiesŌĆÖ amounts to racial segregation and a breach of Article 3.

Self-Determination:

for many observers, the CourtŌĆÖs conclusions on self-determination will have been the least surprising part of this opinion.┬Ā The Court has long had strong credentials on self-determination, having ruled on the concept in various guises at least a dozen times in the years since it was established.┬Ā Nevertheless, the way in which it did so will certainly have raised eyebrows and may in the long term be remembered as one of the most significant parts of this advisory opinion.

The ICJ may, very quietly, very tangentially, have endorsed the argument that Palestine is a State.

The Court held that Israel breached the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination in four key ways:

- By annexing parts of the OPT for settlement building, Israel fragmented the OPT and violated its integrity, in breach of the principle of self-determination;

- By displacing people from parts of the OPT through its settlements and the building of the wall, Israel dispersed the Palestinian population and undermined its right to self-determination;

- By exploiting the natural resources of the territory, Israel breached the right of the Palestinian people to exercise permanent sovereignty over its natural resources, a key aspect of self-determination; and

- That ŌĆśIsraelŌĆÖs policies and practices obstruct the right of the Palestinian people freely to determine its political status and to pursue its economic, social and cultural developmentŌĆÖ, the core of its right to self-determination.

What may be most notable about these findings is that they all draw from the same right of self-determination, which is sometimes called ŌĆśinternalŌĆÖ and sometimes ŌĆśpoliticalŌĆÖ self-determination.┬Ā This is the form of self-determination invoked by the Court in circumstances of political interference, military intervention, or other infringements of the independence of a territory.┬Ā Interestingly, though, it is generally consideredŌĆöespecially following the decision of the ICJ in another of its advisory opinions, concerning KosovoŌĆöthat it only applies to the relations between two States.┬Ā

In other words, the ICJ may, very quietly, very tangentially, have endorsed the argument that Palestine is a State.

WhatŌĆÖs next?

The ICJ didnŌĆÖt say much in its advisory opinion about the current horrendous events in Gaza.┬Ā ThatŌĆÖs not surprising:┬Ā the request for the advisory was submitted to the Court in December 2022, long before the events of the 7th of October 2023, and didnŌĆÖt directly ask it anything relevant to the war being prosecuted there by Israel.

Our focus canŌĆÖt be so narrow.

To the extent that the Court has clarified the status of IsraelŌĆÖs presence in the OPT and might, through law or diplomacy, create new impetus towards a more liveable future for all communities in the region, it is hugely welcome.┬Ā The world can no longer close its eyes to grievous human rights abuses suffered by the Palestinian people of Gaza and the West Bank.

The rule of law requires nothing less. Our humanity demands a great deal more.

But our immediate focus has to remain on the most urgent need.┬Ā Gaza is a killing field.┬Ā Through a hellish combination of Israeli bombs, lack of basic facilities, lack of medical care, and acute and growing food insecurity, GazaŌĆÖs population has been subjected to unimaginable horrors.┬Ā More than 38.000 people have been killed, about a third of them children, and Save the Children has estimated that a further 21.000 children are missing.┬Ā Ninety-six percent of the population of Gaza is now facing acute levels of food insecurityŌĆö2,15 million peopleŌĆöand there are ever-growing warnings about the risk of a full-scale famine.

The ICJ has thrice issued provisional measures orders in the (separate but similar) case brought by South Africa against Israel concerning the events in Gaza, in which the Court has ordered Israel to cease its military operation in Gaza, and to urgently allow food aid, medical supplies, and other emergency humanitarian support into the territory.┬Ā Israel must comply with those orders, and the international community must do much more to bring this intolerable situation to an end.

The rule of law requires nothing less.

Our humanity demands a great deal more.

Related Posts

A Message from Gaza

Victim-Oriented Justice: The International Criminal Court and its Influence on the Situation in Afghanistan

Arms and Aid: Nicaragua’s Call for Action at the ICJ

Beyond the Battlefield: How NGOs Leverage Digital Evidence to Fight Impunity

The effectiveness of provisional measures: South Africa vs Israel┬Ā

1 Comment

Dear Tom,

DoesnŌĆÖt your humanity also compel you to say something about hostages still held in Gaza? About the tens of thousands of Israelis still mourning their dead and internally displaced? How strange.