Jeanette Baumann

Guest Contributor

To read part 1 of this two-part blog post, click here.

It’s a pretty easy equation: the damages and losses suffered due to climate change should be paid by the polluters. It’s only fair.

Polluters pay no more: What are these pledges truly worth?

In broad terms, the Polluter-Pays Principle means that the polluter should be charged with the cost of pollution prevention and control measures. While this principle was originally grounded both in environmental and economic reasonings, taking into consideration above all the scarcity and allocation of resources, approaches concerning intergenerational justice and human rights have taken this principle to a new stage. In more simple terms, the big bad corporations who have been huffing and puffing and burning our planet down and the complicit States who have been idly standing by need to pay up.

Furthermore, while this principle might be considered soft law in nature, it has become clearer that hard laws criminalising environmental damage and crimes akin to “ecocide” like the European Environmental Crime Directive are here to stay with EUR 80-230 billion being lost annually due to environmental crime. The coming economic costs might have incentivised such laws, as they bring about the opportunity for a paradigm change.

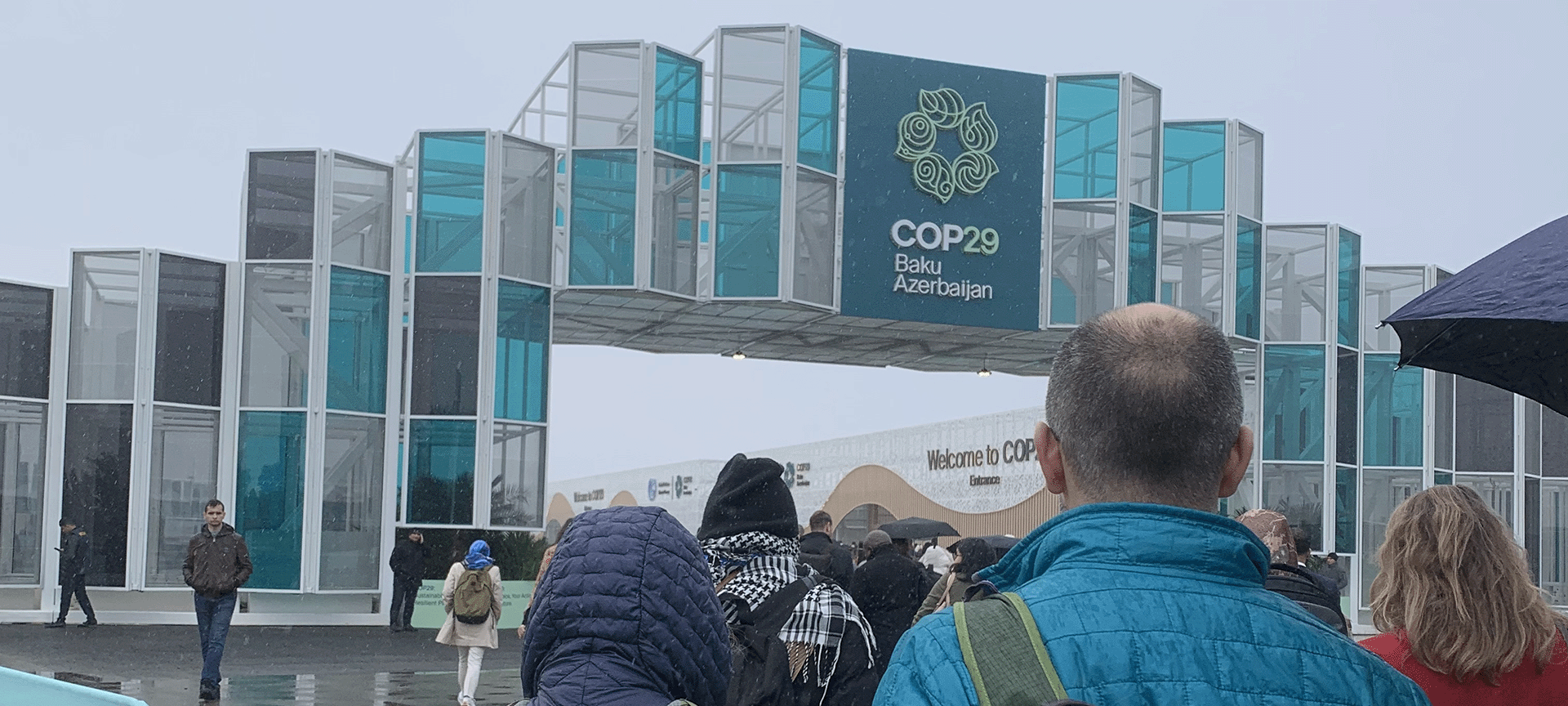

Loss and damage funding is a relatively new point of discussion at COPs, but already the signs are ominous. COP29’s failure to agree to an ambitious, but necessary, goal seems worryingly similar to the ‘Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance;’ this was a global goal set in 2009 whereby States agreed to mobilise USD 100 billion a year by 2020, a target which was only reached in 2022, two years late.

Let’s not forget the relentless fight of grassroots movements for what should be essentially a straightforward process of you pollute, you pay.

Although at COP29 States agreed to a new goal of USD 300 billion annually by 2035, this goal has already been criticised as shamefully inadequate by Global South States and climate activists.¬Ý Additionally, many fear that even this low benchmark will not be met. And yet, one thing is clear: The cost of inaction is immense. The Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) estimates that USD 5.4 trillion to USD 11.7 trillion must be committed per year until 2030, in order to ensure that global temperatures do not rise by more than 1.5¬∞C above the preindustrial average. If loss and damage funding goes the way of the Global Goal it will fail in its purpose of sharing the burdens of climate change.

For instance, over the past 50 years, 69% of global climate-related deaths occurred in the LDCs, which are also home to 17 of the 20 most climate-vulnerable nations. The economic burden is immense, as climate-related losses exacerbate the existing structural challenges like debt distress and a reliance on volatile commodity exports. Many LDCs now spend more on debt repayments than on education and health combined, further hindering their capacity to invest in resilience and development initiatives. These nations also receive an inadequate share of the global climate finance, despite their acute vulnerabilities, leaving them underfunded and under-resourced.

The SIDS and LDCs were betrayed at COP29; they were left to fend for themselves, in the face of a crisis they did not cause.¬Ý While Loss and Damage has always been a question of justice, the Loss and Damage Fund has become a symbol of the inequities of the climate crisis. In what may be the biggest snub in COP history since Copenhagen, justice hasn‚Äôt been served at COP29 as the very States that are least able to cope with climate change‚Äôs effects are those who will bear the brunt of its devastating impacts.

Progress must come from the bottom up

Let’s not forget the relentless fight of grassroot movements for what should be essentially a straightforward process of you pollute, you pay.

The Loss and Damage Fund (FRLD) and the climate finance system as a whole are broken. But does that mean all is lost?¬Ý The path to more equitable climate finance lies in a human rights-centred approach with just remedies and compensation based on the science of attribution. Human rights and climate change are intricately intertwined and all steps forward should be grounded in principles such as equity, climate justice, social justice, inclusion, and a just transition.

To effectively address the challenges faced by vulnerable countries and communities, States must demonstrate greater ambition and political coherence. This involves increasing financial resources and adopting a needs-based approach tailored to the specific challenges of those most affected by climate change and development issues. Additionally, there is broad agreement on the importance of reforming the financial rules to better account for the unique difficulties encountered by developing nations.

This can’t work without simplifying access to finance and capacity building. For example, the LDCs at COP29 complained that it takes three years to access funds, which unnecessarily hampers effective responses and ambitious projects. Streamlining bureaucratic barriers to accessing climate finance is therefore a priority, especially for SIDS. In turn, capacity building is also key: strengthening institutional capacities for data collection and risk analysis is a necessary step, as is strengthening the response to the impacts on the ground.

It is well evidenced that the perpetual cycle of debt hinders progress, leading to a response and dependency, but not meaningful, sustainable change. UNCTAD, using IMF data and the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index of 2020, reportedly indicates that almost half of low-income nations face significant risks related to both debt and the climate crisis. Additionally, a report by the Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery Project highlights that among the 66 economically vulnerable emerging markets and developing economies, 47—accounting for a population exceeding 1.11 billion—are likely to encounter insolvency within the next five years if they attempt to increase investments to achieve climate and development objectives. Therefore, rather than exacerbating the existing fiscal vulnerabilities, the importance of grants and other non-debt mechanisms cannot be overemphasised.

Moreover, engaging the private sector could play a crucial role in bridging the existing financing gap, particularly in areas like sustainable development and climate action. Impact investing, which focuses on generating both social and environmental benefits alongside financial returns, represents a promising approach in this regard. However, the effectiveness of such efforts depends on the development of robust frameworks that encourage and incentivise private sector participation, ensuring investments align with broader development goals but also adhere to transparency and human rights principles.

Future COPs: For now, all eyes on Belém

Finance was one of the core themes of the COP29, but it missed its mark. From procedural misconduct to a lack of ambition, States have failed to deliver critical changes. Our eyes are now looking to Belém. Brazil has its own unique challenges like deforestation, wildfires, droughts, and ultimately achieving a just transition from fossil fuels, but the road to a COP is paved with opportunity.

If Baku has shown us anything, it’s that we don’t have too many ‘next years’ left.

Brazil continues to show ambition to reduce deforestation. Since Luiz In√°cio Lula da Silva replaced Jair Bolsonaro deforestation has gone down by more than 60%, and continues to fall.¬Ý Although further progress is needed as there is no safe level of deforestation in the Amazon, perhaps Brazil‚Äôs successful record will translate into strong and effective moral leadership at the COP.

An Amazon COP also provides an opportunity for indigenous participation. While they protect more than a quarter of the world’s land surface across 87 countries, local communities and indigenous people have been routinely ousted from participation in international climate fora. Their practices, knowledge, and solutions are routinely devalued, and their presence is seemingly valued more so for the photo opportunity it provides than anything else. With 385 indigenous groups calling the Amazon rainforest their home, the case for indigenous inclusion at a COP has never been stronger. Indigenous people must be centre stage, and the values of solidarity and environmental stewardship which they exemplify must be amplified by all.

We cannot afford to always be looking to ‚Äònext year‚Äô, ducking the difficult choices, putting off the hard decisions, and going back to fix the bad compromises of previous years.¬Ý If Baku has shown us anything, it‚Äôs that we don‚Äôt have too many ‚Äònext years‚Äô left.