Fitri Lestari

Legal Intern

Global migration is pivotal to human societies and increasing at an exponential rate. As of 2020, the United Nations estimated there were approximately 281 million international migrants and that women, constituting approximately 48 percent of this population, are assuming an increasingly prominent role.┬Ā┬Ā

Referred to as the feminisation of labour migration, the increase in women migrant workers represents a highly influential pattern in current global migration. Driven by the escalating demand for cheap labour and the docile labour power of women, forces of patriarchy and capitalism encourage the trend of feminizing labour and migration. It is the demand for ŌĆ£womenŌĆÖsŌĆØ work that pushes the labour and migration of women throughout globalisation, as richer countries abroad seek low-wage, docile, domestic workers to exploit. ┬Ā

In Indonesia, World Bank records indicate there are more than 9 million Indonesian citizens who are now working overseas. The majority of them are women; and 32 percent work in the domestic sector, which is private and invisible from public scrutiny. In the last five years, data from Badan Pelindungan Pekerja Migran Indonesia/BP2MI (the Indonesian Migrant Workers Protection Agency) shows 71 percent of Indonesian migrant workers are women. ┬Ā

They face triple discrimination because their gender is woman, their status is working class, and their nationality is a migrant. Xenophobia and racism have never escaped them.

The Vulnerability of Women Migrant Domestic Workers ┬Ā

In this trend of the feminization of labour migration and under this patriarchal society, Indonesian women migrant domestic workers experience increased vulnerability to exploitation, trafficking, modern slavery, and discrimination. They face multiple forms of gender-based violence, including physical, psychological, and sexual violence, sexual exploitation, femicide, and other human rights violations. This violence not only occurs in the country of destination but also in the country of origin and transit. Moreover, they face triple discrimination because their gender is woman, their status is working class, and their nationality is a migrant. Xenophobia and racism have never escaped them.┬Ā┬Ā

The experiences of Indonesian women migrant domestic workers are increasingly haunting because of their unique vulnerability. Particularly since, despite consistently facing flagrant and violent violations of their rights, they experience difficulties accessing justice. Language barriers and international isolation by employers ŌĆō who often confiscate their passports and cell phones, and confine them to employer housing to ensure they cannot run away ŌĆō force women to stay and accept these circumstances or take drastic measures to escape. Only to face the real chance of being revictimised by the system if they do, as a result of a lack of adequate legal protections. In Saudi Arabia, one Indonesian woman migrant domestic worker was executed for murdering her employer, despite the fact that she was being sexually abused and acted in self-defence. ┬Ā

Violent Experience, Heroic Portrayal┬Ā┬Ā

Yet, Indonesian migrant workers are the agents of development. They contribute to social and economic development, not only for their families, but also for their towns, cities, and country, both in their country of origin and country of destination. Research from the World Bank shows that labour migration contributes directly to improving peopleŌĆÖs lives. In Indonesia, there is a term for Indonesian migrant workers, so-called ŌĆśheroes of foreign exchangeŌĆÖ or pahlawan devisa. In 2016, migrant workers sent over IDR 118 trillion (US$8.9 billion) back to Indonesia in remittances. ┬Ā

Migration takes women outside the private sphere, but, ironically, their paid labour as care workers usually places them back inside the private sphere, where protections are minimal to non-existent.

The International Organization of Migration states that studies indicate that women, despite typically earning lower incomes than men, exhibit a higher tendency to allocate a greater proportion of their earnings towards remittances. Moreover, women tend to send money on a more frequent and sustained basis. However, the benefits from Indonesian women migrant workersŌĆÖ contributions have not led to better protections. Rhacel Salazar Parre├▒as, a Professor of American Civilization at Brown University, argues that migration takes women outside the private sphere, but, ironically, their paid labour as care workers usually places them back inside the private sphere, where protections are minimal to non-existent.┬Ā

Migration has always played a significant role in human history. It has supported the process of global economic growth, contributed to the evolution of states and societies, and enhanced the richness and diversity of numerous cultures and civilizations. Yet, States like Indonesia continue to neglect the protection of these womenŌĆÖs rights.┬Ā

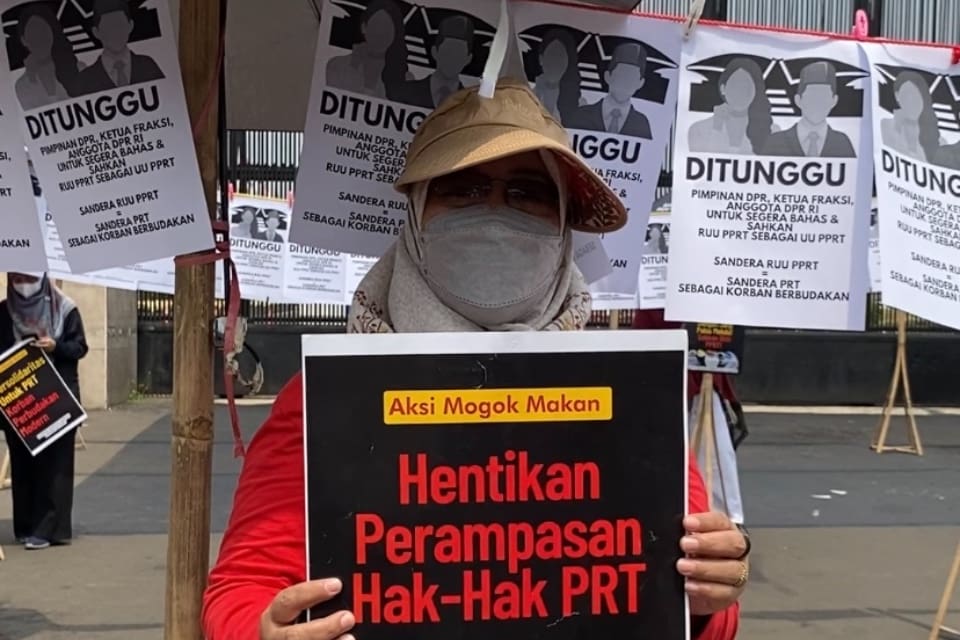

Translation: “Domestic Workers’ Hunger Strike. Stop the Violation of Domestic Workers’ Rights”

Source: konde.co

The Urgent Need to Pass the RUU PPRT┬Ā

Indeed, in Indonesia, care work is not yet subject to adequate legal protections. Women are looked down upon, portrayed as having no economic value and no skills, and are not considered a part of nor contributors to public life. Domestic labour ŌĆōsynonymous with womenŌĆÖs work ŌĆō is not considered a job. ┬Ā

┬Ā

┬Ā

To ensure essential protection for domestic workers abroad (migrant domestic workers), along with domestic workers in Indonesia, the Government of Indonesia should provide recognition, protection, and respect for their rights by ratifying the Bill of Protection for Domestic Workers and ILO Convention No. 189 concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers.

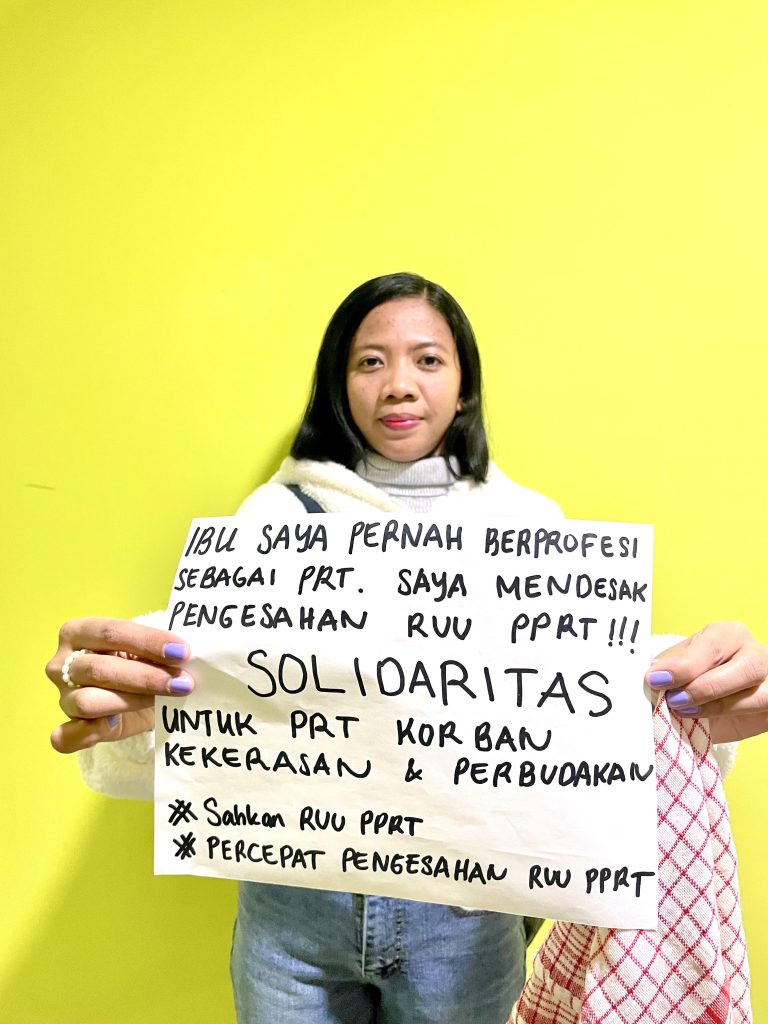

The situation in Indonesia exacerbates the vulnerability of domestic workers abroad. To ensure essential protection for domestic workers abroad and in Indonesia, the Government of Indonesia should provide recognition, protection, and respect for their rights by ratifying the Bill of Protection for Domestic Workers (Rancangan Undang-Undang Pelindungan Pekerja Rumah Tangga/RUU PPRT) and ILO Convention No. 189 concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers.┬Ā

For 20 years, civil society organizations, including domestic workers and migrant domestic workers organizations, vehemently advocated for these types of protections, mainly by calling for the Government of Indonesia to ratify these legal protections. The National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan) also urged the Government of Indonesia to promptly discuss and ratify RUU PPRT by the end of the 2019-2024 House of Representatives working period, which concludes in October 2024. Unfortunately, the House of Representatives did not ratify the RUU PPRT this year. The bill has now been carried over and will be part of the priority national legislative program for the 2024-2029 period. Civil society organizations and the national human rights institution have expressed regret over the HouseŌĆÖs failure to pass the RUU PPRT during this term.┬Ā

┬ĀRatification relies on the political willingness of Indonesian government officials. If ratified, it would be a huge step forward for domestic workers. By providing recognition of status, RUU PPRT and ILO Convention No. 189 would ensure legal guarantees and certainty, preventing discrimination, and protecting the rights of domestic workers. These laws provide protections for issues ranging from wages and working time to human trafficking. Legal recognition and protection ensure that domestic workers are entitled to the same rights as other workers.┬Ā

It also provides an opportunity for Indonesia to follow the example of the Philippines, which ratified the ILO Convention and passed national legislation protecting these rights. Overall, the ratification of RUU PPRT will protect the rights of Indonesian domestic migrant workers in the territory of Indonesia and ILO Convention 189 will strengthen these protections at the international level.┬Ā

Translation: “My mother worked as a domestic worker. I urge the ratification of the Bill of Protection for Domestic Workers” (RUU PPRT).

A Bilateral and Multilateral Agreement and Cooperation with the Countries of Destination┬Ā

To enforce legal provisions effectively, it is imperative for the Government of Indonesia to fortify the safeguarding measures for women migrant domestic workers. This can be accomplished by forging robust bilateral and multilateral agreements with destination countries employing Indonesian domestic workers, including Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and others. Such agreements would ensure comprehensive protections and uphold the rights of these vulnerable individuals in a manner befitting their contributions to the global workforce.┬Ā┬Ā

The ratification of RUU PPRT and ILO Convention No. 189 would mark a significant turning point in fortifying protections of women domestic workers’ rights, not only within Indonesia but also during transit and in the destination countries. Such legislative advancements would serve as a beacon of commitment to upholding the fundamental rights of women and garner due respect from other nations. Moreover, it would acknowledge the invaluable worldwide contributions of women domestic workers, extending beyond their role in the domestic sphere to encompass their meaningful engagement in the political, social, cultural, and economic realms.┬Ā